Managing inventory in a manufacturing business is a constant balancing act. You need enough raw materials to keep production running, but not so much that cash is tied up on shelves. You want work-in-progress (WIP) moving swiftly on the shop floor, but not accumulating in piles and causing bottlenecks. And you must have sufficient finished goods ready to meet customer demand, but not an overstock that inflates storage costs.

Striking the right balance among raw materials, WIP, and finished goods inventory is crucial for efficiency, cash flow, and customer satisfaction in manufacturing operations.

Understanding the Three Types of Inventory in Manufacturing

In a manufacturing context, inventory isn’t a single monolithic concept – it comprises distinct categories, each serving a purpose in the production cycle. Let’s briefly define the three key types of inventory in manufacturing and what role they play:

- Raw Materials: These are the base materials, components, or sub-assemblies that will be used to create your products. Raw materials could be things like steel, plastic resin, electronic components, fabric, chemicals, or any input that hasn’t yet been processed into the final product. They are the first stage of inventory, sitting in storage until needed for production. Managing raw material inventory means ensuring you have the right materials on hand at the right time, without hoarding so much that they become obsolete or consume excess capital.

- Work-in-Progress (WIP): WIP inventory includes items that have entered the production process but are not yet completed. This could be partially assembled products on an assembly line, sub-components in intermediate stages, or batches of goods in the middle of processing (for example, a batch of soup being brewed before it’s canned, or fabric pieces cut and awaiting stitching). WIP is essentially “in-transit” between raw and finished state – it’s value that is still being added. Managing WIP is about keeping production flowing smoothly, monitoring each stage so nothing gets stuck, and avoiding too much work piling up unfinished.

- Finished Goods: Finished goods are the completed products ready for sale or shipment to customers. These sit in your finished goods warehouse or storage area awaiting distribution. Finished goods inventory management focuses on storing products safely, keeping them ready to fulfill orders, and ensuring they don’t linger so long that they incur high holding costs or risk obsolescence. Finished inventory is what eventually generates revenue, but until sold, it represents cash locked in stock.

Each type of inventory is essential to manufacturing, and they are tightly interconnected. Raw materials feed WIP; WIP becomes finished goods; and finished goods fulfillment drives the need for more raw materials. Imbalances in any one area can ripple through and hurt the entire operation. In the next sections, we’ll dive into why balancing these inventory levels is critical and what can go wrong when they’re out of sync.

The Importance of Balancing Inventory Levels

Maintaining the right balance of raw materials, WIP, and finished goods is critical for a healthy manufacturing operation. If any one of these categories is out of proportion, it can lead to a range of problems – from production delays and lost sales to excessive costs and cash flow strain. Let’s look at why balancing inventory matters by considering each category:

Raw Materials: Too Little vs. Too Much

Running out of raw materials is every production manager’s nightmare. If you don’t have the necessary materials when you need them, production can grind to a halt. A single missing component can idle an entire assembly line full of workers and machines. The result: unfilled orders, frustrated customers, and emergency expediting (often at high cost) to get production going again. In short, too little raw material inventory can cause stockouts, production downtime, and lost revenue.

On the other hand, excess raw material stock comes with its own set of pains. Ordering far in advance or in bulk beyond what’s needed ties up working capital in materials that just sit in a warehouse. Those materials incur carrying costs – you pay for storage space, handling, and insurance, and some materials might have shelf-life or become obsolete. For example, ordering a six-month supply of a specialized component might secure a bulk discount, but if design changes or demand drops, you’re stuck with expensive stock that may never be used. Thus, too much raw inventory drains cash, increases storage costs, and risks waste.

The goal is to strike a balance: have enough raw materials on hand to meet production needs (and a cushion for safety) but not so much that you’ve essentially turned your money into idle stock. Achieving this requires good demand forecasting, supplier coordination, and inventory planning (which we’ll discuss shortly).

Work-in-Progress (WIP): Finding the Flow Sweet Spot

WIP inventory is a bit of a Goldilocks problem – you don’t want it too high or too low. Excessive WIP often indicates inefficiencies in your production process. If partially finished goods are piling up between workstations or waiting in long queues, it means production flow is not smooth. High WIP can be caused by bottlenecks at a certain machine, mismatched production rates in different departments, or batch processes that release large chunks of work that then sit idle. The consequences of too much WIP include: extended production lead times, increased chances of damage or loss while items wait, difficulty tracking orders, and a lot of cash tied up in half-complete products.

Essentially, that money cannot be recovered until the WIP becomes finished product and gets sold, which lengthens your cash conversion cycle (the time it takes for money spent on inventory to return as sales revenue).

Moreover, high WIP can hide problems. When there’s a queue of jobs, issues like quality defects or machine downtime might get masked because upstream processes keep working and piling up inventory. It gives a false sense that everything is running, whereas in reality, there’s a clog in the pipeline. Too much WIP = slower throughput and less agility, as well as higher inventory carrying cost without yet producing sellable goods.

Conversely, too little WIP means each stage of production has minimal buffer. In an ideal lean world, zero WIP sounds great – it means each item flows directly from start to finish without waiting. In practice, though, having some WIP is often necessary to decouple process steps and ensure one slower step doesn’t starve the others immediately. If WIP is kept extremely low and tightly controlled, any small hiccup (like a machine breakdown or a short delay in one step) could lead to the next stage being starved of input and the line going idle. In other words, too little WIP without careful coordination can make your process fragile to disruptions.

The key is finding the “just right” WIP level that keeps everything moving steadily. You want enough WIP to absorb minor variability and keep workers busy, but not so much that it creates long delays or hides systemic issues. Techniques like setting WIP limits at each workstation (as used in Kanban systems) help maintain this balance by preventing any station from getting overloaded.

Finished Goods: Balancing Availability and Overstock

For finished goods inventory, the stakes are directly customer-facing. Insufficient finished goods stock means you may not be able to fill orders promptly. Customers today expect on-time delivery; if you’re constantly backordered because you only produce to order or you mis-forecasted demand, you risk losing business. In manufacturing, especially B2B, failing to ship products as promised can damage client relationships and your reputation for reliability. So having some finished goods ready (or a short lead time to make them) is important for good service levels. Too little finished stock can lead to stockouts, missed sales opportunities, and unhappy customers.

However, excess finished goods sitting in the warehouse is a classic sign of overproduction or demand overestimation – one of the major forms of waste in lean manufacturing philosophy. If your warehouses are full of products that aren’t selling, you face multiple problems. You incur high storage costs and potentially need to rent extra space. Products might become obsolete if newer models come out, or perishable goods can expire. Even durable goods can suffer from damage or packaging deterioration over long storage periods. Plus, inventory on the books as finished goods is essentially money that’s not generating any return – it’s capital tied up that could have been used elsewhere.

In some industries, excess finished goods lead to having to heavily discount products to clear them (hurting margins) or scrapping items altogether if they become unsellable. For instance, a manufacturer that built 10,000 units of a gadget expecting a big order, only to have it pushed out or canceled, might find those units sitting for months. During that time, not only is cash locked up, but the company might be paying for insurance and warehousing, and possibly seeing the product’s market value erode as newer tech comes along. Too much finished inventory can turn into a liability, despite being listed as an asset on the balance sheet.

So, balancing finished goods is about meeting the demand promptly without overproducing. It requires accurate sales forecasting, agile production planning, and close coordination between the production team and sales/marketing so that you make what can be sold in a timely manner.

The Cost and Cash Flow Impact

Beyond the individual issues above, it’s worth noting how inventory balance affects financial performance. Inventory, whether raw, WIP, or finished, represents capital. Purchasing raw materials consumes cash; adding labor and overhead turns raw into WIP and finished goods (increasing their value). Until finished products are sold and paid for, all that money is locked inside your inventory. Therefore, heavy inventory levels mean a longer cash cycle – more time between paying your suppliers and getting paid by customers.

An imbalance like overstocking any inventory will directly hurt cash flow. You may find yourself “rich on paper” (lots of assets in inventory) but “poor in cash” – unable to invest in other opportunities or sometimes even struggling to pay bills because so much money is sitting in stock. Balancing inventory levels helps free up liquidity. For example, reducing excess raw materials and WIP can shorten the production cycle and reduce the days inventory outstanding. And on the flip side, failing to hold enough inventory at critical points can cause lost revenue that also hits the bottom line.

In short, effective inventory balance is a cornerstone of operational efficiency and financial health for manufacturers. It ensures smooth production with minimal interruption, keeps costs in check, and helps convert investment into revenue faster. Now that we’ve covered why it’s so important, let’s look at best practices to achieve the right balance for each inventory category.

Best Practices for Managing Raw Material Inventory

Controlling raw material inventory is about having the right materials, at the right time, in the right quantity. This can be challenging when dealing with multiple inputs, supplier lead times, and fluctuating demand, but a few proven practices can significantly improve your raw material management:

- Accurate Demand Forecasting: Start with a solid forecast of what your production needs will be. Use historical production data, sales forecasts, and market trends to predict how much of each raw material you’ll need in upcoming weeks or months. Good forecasting prevents both shortages and over-ordering. For example, if you know certain product sales are seasonal, you can plan raw material purchases to ramp up or taper down accordingly. Regularly update forecasts and align them with your materials purchasing plan.

- Establish Reorder Points and Safety Stock: Determine for each critical raw material a reorder point – the inventory level at which you must trigger a replenishment order to avoid running out. This calculation typically accounts for your supplier’s lead time and your average usage rate. In addition, keep a safety stock buffer for key materials to absorb demand spikes or supplier delays. The safety stock is an extra quantity maintained to reduce the risk of stockouts. By setting clear reorder points and safety stock levels, you’ll get timely alerts to restock before you hit a crisis, ensuring production isn’t caught empty-handed.

- Just-In-Time (JIT) Ordering (Where Feasible): Many manufacturers implement elements of Just-in-Time inventory strategy for raw materials. JIT means scheduling inbound materials to arrive right when they are needed in production (or as close as possible), rather than storing big piles for weeks. If you have reliable suppliers and predictable production schedules, JIT can dramatically reduce raw material holding costs. You’re essentially transferring the storage burden back to the supplier until the last moment. However, JIT requires trust and coordination with suppliers, and a backup plan for any disruptions. Even if full JIT isn’t possible, working with vendors on smaller, more frequent deliveries can help prevent overstocking.

- Organize and Prioritize (ABC Analysis): It’s wise to categorize your raw materials by importance and usage frequency. ABC analysis is a technique where you divide inventory into three groups: “A” items are high-value or critical materials (small in number but large impact), “B” are moderate, and “C” are lower value or very common items. Focus your tightest control and frequent monitoring on the A items – those where a shortage would be very damaging or that cost a lot of money. Ensure A items have secure supply lines and maybe higher safety stock. For B and C items, you can manage with simpler methods (like periodic reviews or two-bin systems for C items). This prioritization ensures you allocate your attention and resources efficiently, guarding against problems in the most crucial materials.

- Strong Supplier Management: Your relationship with suppliers plays a huge role in raw inventory management. Build partnerships with reliable suppliers, and consider sharing your demand forecasts with them. By collaborating, suppliers might offer flexible arrangements like consignment inventory (you pay when you use it), vendor-managed inventory, or simply more accommodating minimum order quantities. Negotiating smaller batch deliveries or shorter lead times can prevent you from having to overstock. Also, have secondary suppliers for critical items to reduce dependency on a single source. Good communication means suppliers can warn you of any delays early or maybe expedite if you’re in a pinch.

- Inventory Tracking and Visibility: Keep your raw materials well-organized in the warehouse and track them diligently. A chaotic storage area can lead to parts getting lost, damaged, or expired without anyone noticing. Use an inventory management system or at least a spreadsheet to log all receipts and usages of raw materials. Implement barcoding or RFID scanning if possible, to quickly update stock levels as materials are consumed. Physical organization matters too: store raw materials in designated areas, labeled clearly, with fast-moving materials closer to the production floor for quick access. This reduces wasted time and helps maintain accurate counts. Regular cycle counts (routine partial stock counts) or periodic full inventories will catch any discrepancies between records and actual stock, so you can adjust and investigate causes (like usage errors or shrinkage).

- Optimize Order Quantities (EOQ): When ordering raw materials, it’s important to balance the cost of ordering with the cost of holding inventory. The Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) formula can help determine the optimal purchase quantity that minimizes total inventory cost. EOQ considers factors like your annual usage of the material, the fixed cost of placing an order, and the carrying cost per unit. While you don’t need to do complex math for every item, understanding the principle will guide you. Ordering in bulk may reduce price per unit, but if those savings are smaller than the cost of storing the excess for months, it’s not truly economical. Find the sweet spot where ordering and carrying costs are lowest.

- Quality and Shelf-Life Management: Don’t overlook the quality aspects of raw materials. If materials have expiration dates (chemicals, food ingredients, etc.) or can degrade over time (like electronic components sensitive to moisture), managing inventory so that old stock is used first is vital. FIFO (First In, First Out) should be the rule: use your oldest batches of materials in production before the newer ones, to avoid spoilage or obsolescence. Also, inspect incoming raw materials for quality – subpar inputs can lead to production scrap and unexpected shortages if you have to throw material away. A good practice is to involve your quality control team in inventory management: they can advise on how long certain materials remain usable and help monitor storage conditions.

By implementing these practices, manufacturers can maintain a lean yet reliable raw material inventory. The outcome is a steadier production process with fewer emergency scrambles, lower holding costs, and better use of capital.

Best Practices for Managing Work-in-Progress (WIP)

Work-in-progress inventory can be tricky to manage because it’s not as visible as raw materials or finished stock sitting on shelves. WIP is spread out across the factory floor, in machines, in bins between steps, or even in transit between facilities. The key objective with WIP is to keep it flowing smoothly. You want to avoid both excessive build-up and frequent stoppages. Here are some best practices to manage WIP effectively and maintain a balanced production flow:

Map Your Production Process and Identify Bottlenecks: First, gain a clear view of your production stages and how work moves through them. Create a simple map or diagram of each step required to turn raw materials into finished product. Then, assess the capacity and cycle time of each step. Often, you’ll find that one step is slower or has less capacity than the others – this is your bottleneck, where WIP tends to accumulate. For example, if you have three assembly stations and the second one takes twice as long as the first and third, products will pile up before station two. Identifying these choke points is the first step to controlling WIP. You can then take actions like adding resources at the bottleneck, splitting the task, or adjusting workloads to balance the line. Remember the adage from the Theory of Constraints: the system output is determined by the slowest part. By elevating or managing the bottleneck, you prevent endless WIP growth in that area and increase overall throughput.

Set WIP Limits (Kanban/CONWIP Systems): A proven lean manufacturing technique is to explicitly cap the amount of work allowed in process at each stage. This is often implemented with Kanban cards or a CONWIP (Constant Work-in-Progress) approach. For instance, you might decide that station A should have no more than 10 units in its input queue and 5 in progress at any time. If it hits that limit, upstream processes must pause until some work clears. These WIP limits act like traffic signals, preventing any single station from being flooded. It forces a synchronization – upstream can’t overproduce and downstream won’t be starved because upstream is busy with too many things at once. Start by setting WIP limits based on current averages or what seems reasonable for each step, then fine-tune. Operators and supervisors should be aware of these limits and treat them as triggers: if a buffer is full, it’s time to stop producing more and instead help clear the bottleneck. This discipline keeps your WIP at a manageable level and quickly surfaces any flow problems that need attention.

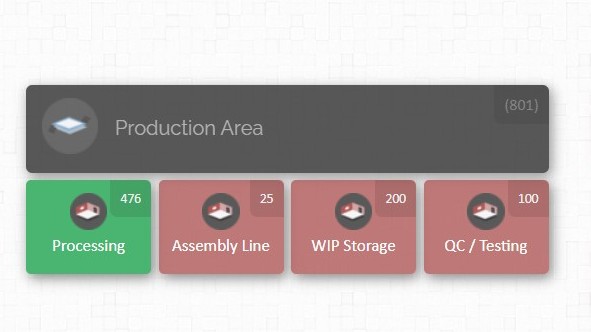

Make WIP Visible: As the saying goes, “you can’t manage what you don’t see.” If WIP is scattered and not tracked, it’s easy to lose track of partially finished orders, or to not realize how much is stuck waiting. Implement visual management tools for WIP. This could be as simple as a whiteboard or digital dashboard showing each production stage and how many units (or which orders) are currently there. Some factories use cardboards or electronic displays above each station to show the queue length. Modern software (like Manufacturing Execution Systems or inventory mapping tools) can display a real-time view of WIP across the floor.

The idea is that at a glance, you and your team should know exactly what’s in progress and where. For example, color-code orders and use markers when an order has been sitting too long at a step. Visibility empowers quick decision-making: if you see one station’s queue growing, you can react by reallocating labor or investigating the holdup. It also fosters accountability – each team sees their role in the bigger flow.

Track Cycle Times and Tackle Blockers: Keep a close eye on cycle time (how long it takes for one unit to go through each step or the whole process) and throughput (how many units are completed in a period). If cycle times start creeping up without an increase in output, it’s a sign that WIP is probably growing – things are taking longer, likely waiting somewhere. When work does stall, don’t just push it through blindly; find out why.

Encourage operators to flag and record reasons for any stoppage or delay. Common blockers might include waiting for a missing part, a machine breakdown, a quality issue that needs rework, or even waiting for a batch to accumulate. By gathering data on these occurrences, you’ll likely see patterns. Maybe a particular part frequently isn’t available on time (pointing to a supply issue or a scheduling mismatch), or perhaps a certain machine is causing frequent delays (indicating maintenance or capacity addition is needed). Root cause analysis on WIP blockers can lead to fixes that improve flow and reduce ongoing WIP buildups.

Balance the Production Line: Strive for a smooth, balanced production line where each process stage takes around the same amount of time (or capacity is matched to demand). This might involve cross-training workers so they can assist slower stations when needed, or investing in faster equipment for a chronically slow step.

Techniques like line balancing during production planning can help: divide work elements such that each workstation has a roughly equal amount of work content time. If perfect balance isn’t possible (it rarely is), use small buffers in front of slower stations, but control their size with the WIP limits as mentioned. Also, consider running smaller batch sizes – large batches often create surges of WIP. Smaller, more frequent batches (or one-piece flow where viable) keep WIP levels low and lead times short.

Implement Just-in-Time and Pull Systems: Extending JIT beyond raw materials, apply its principles inside the factory as well. A pull system means each workstation only produces when the next station signals a need (rather than push work downstream regardless of whether it’s needed immediately). By using Kanban cards or electronic signals between processes, you create a “pull” where downstream demand drives upstream production. This naturally limits WIP because if final assembly isn’t consuming units, nothing should be pushing more units into the system unnecessarily.

JIT in production could also involve synchronizing production rates with actual customer orders (build-to-order where possible) so that you’re not creating piles of semifinished goods without clear demand. Adopting JIT thinking ensures that WIP is only created when it’s truly required, reducing excess accumulation.

Continuous Improvement on the Shop Floor: Finally, treat WIP levels as an important metric to continually improve. Encourage a culture of continuous improvement (Kaizen) where the team regularly looks at how to reduce waste in the process. High WIP is considered one of the seven wastes (“inventory”) in lean methodology, so it’s a prime target for elimination. Hold brief weekly meetings or daily stand-ups with production leads to review if any station had unusual WIP buildup or downtime, and brainstorm solutions.

Over time, these incremental improvements – whether it’s rearranging the layout to reduce transit time, tweaking a machine’s settings to reduce rework, or adjusting staffing during peak periods – will keep WIP under control. You’ll notice that as WIP goes down, many other good things happen: product moves faster, quality issues surface and get solved faster, and everyone has clearer focus on what needs to be done next.

Efficient WIP management ensures that your partly finished goods spend minimal time waiting around. The payoff is a shorter manufacturing cycle, lower WIP costs, and the flexibility to respond quickly to new orders or changes. Now, with raw materials and WIP covered, let’s move to best practices for finished goods – the final output of all your efforts.

Best Practices for Managing Finished Goods Inventory

Finished goods inventory sits at the end of your production pipeline, and it directly affects your ability to fulfill customer orders swiftly. The challenge is to keep enough stock of each product to meet demand (and buffer against variability), but not so much that you inflate costs or risk having unsold products. Here are some best practices to manage finished goods inventory wisely:

- Align Inventory with Demand Forecasts: Just as forecasting is vital for raw materials, it’s equally critical for finished goods. Use sales data, market trends, and customer forecasts to plan how many units of each product you should keep in stock. If you have historical sales data, analyze patterns: Are there seasonal peaks? Certain product lines growing or declining? By forecasting demand, you can set target stock levels for finished goods that will cover the expected sales until the next production run. Regularly update these forecasts – they are living estimates and should be adjusted as new information comes (e.g., a major new order, a market slowdown, etc.). A close collaboration between the sales/marketing team and the production planning team is essential here. The goal is to produce to actual demand as much as possible, rather than to a wild guess, thereby reducing the chance of large surpluses or shortages.

- Establish a Finished Goods Reorder/Production Point: Similar to raw materials reorder points, if you operate a make-to-stock model, set a replenishment trigger for finished goods inventory. For example, if you want to always have 500 units of Product X available and it takes 2 weeks to produce a batch, you might decide to start production of more units when stock hits, say, 300 units (accounting for expected sales during those 2 weeks and a safety buffer). This way you replenish before hitting zero. In a make-to-order or assemble-to-order scenario, you might keep lower finished stock but maintain some WIP or semi-finished components that can quickly be turned into finished goods when orders come. The right approach depends on your production lead time and customer tolerance for wait times. Regardless, have a plan for when and how to trigger production to restock finished inventory.

- Monitor Inventory Turnover and Aging: Keep an eye on inventory turnover ratio for your finished goods. This metric tells you how many times your inventory is sold and replaced over a period (usually a year). A low turnover means items are sitting too long; a high turnover means you’re selling quickly relative to stock (which is good as long as you’re not stocking out). Additionally, track aging of inventory – how long each batch or SKU has been sitting in the warehouse. Implement a FIFO (First-In, First-Out) system for shipping products out, so older products sell first (this prevents old stock from gathering dust while only new stock moves). If you find items that have been in storage for an unusually long time (say, beyond a certain threshold like 6 months or a year depending on your product), that’s a red flag. Those might be slow-moving or obsolete. You can then take action: investigate why they aren’t selling, consider promotions or discounts to clear them, or in worst case, plan to discontinue or write off if necessary. Regular review of aging inventory helps avoid nasty surprises of big write-downs later.

- Optimize Production Batch Size and Frequency: One reason companies end up with excess finished goods is producing in overly large batches for efficiency’s sake. While big production runs can lower unit costs (due to economies of scale or reduced setups), they also create a lot of inventory at once. It might be wiser to do smaller, more frequent production runs for items with moderate or uncertain demand. This way, you can adjust to actual sales trends more nimbly and prevent massive piles of unsold goods. Look into strategies like quick changeover techniques (SMED) to reduce setup times, which then allows economically viable smaller batches. The lean manufacturing ideal of “make one, sell one” (i.e., make exactly what’s needed when needed) is tough to achieve perfectly, but moving in that direction with reduced batch sizes can significantly cut down finished inventory without harming service levels.

- Maintain Safety Stock for Key Products: Just as with raw materials, having a bit of safety stock for finished goods can be a lifesaver for demand spikes or supply disruptions. Identify your best-selling or most critical products – the ones customers must receive on time, or those with unpredictable surges – and keep a safety buffer of those finished items. This ensures you can absorb an unexpected large order or a seasonal rush without immediately going to backlog. However, be strategic – safety stock is extra money on the shelves, so you want it on items that truly justify it (for example, your top 5 revenue-generating products, or products with very erratic demand where a buffer is the only way to ensure availability). For lower value or predictable items, you might choose to have zero or minimal safety stock and instead rely on your efficient production to refill as needed.

- Utilize Inventory Analytics and Metrics: Leverage any tools you have (in your ERP, inventory management software, or even spreadsheets) to analyze your finished goods data. Metrics to watch include Days of Inventory (DIO) which tells how many days’ worth of sales is sitting in inventory, or the fill rate which measures what percentage of customer orders are fulfilled immediately from stock. A high DIO means you have lots of stock relative to sales (potential overstock), while a low fill rate means stockouts are frequent (potential understock). Try to balance these metrics: you want a high fill rate (good service) with a reasonably low DIO (efficient inventory). Also analyze item-by-item performance: some products might be consistently overstocked. This could indicate you need to cut production on those or even consider phasing them out if demand isn’t meeting expectations (a practice known as SKU rationalization – trimming the product line to eliminate underperformers can free up resources and space).

- Coordinate with Sales and Marketing: Sometimes, inventory issues can be addressed on the demand side too. If you find yourself with excess finished goods, loop in the sales and marketing team. They might run promotions, bundle offers, or push those products more to customers to help clear inventory. Conversely, if demand is stronger than expected and you risk running out, they should know so they don’t aggressively promote something you can’t supply, or so they can manage customer expectations (or pricing). Frequent communication between the operations side (which manages inventory) and the commercial side ensures that both sides work in tandem. For example, before launching a big sale or new campaign, marketing can check if there’s enough product in stock or give a heads-up to production to ramp up. Aligning these efforts prevents a lot of headaches and helps maintain the right inventory balance from both directions.

- Plan for End-of-Life and New Introductions: In industries where products have lifecycles (electronics, fashion, automotive, etc.), finished goods management must account for product transitions. If a product is nearing its end-of-life or a new model is coming, carefully manage the wind-down of the old inventory. You want to avoid being stuck with large stocks of an outdated product. This might mean gradually reducing production as the new version’s launch date approaches, or offering discounts to deplete old stock. Similarly, for new products, don’t overproduce out of excitement – start with modest inventory until the market response is clear, but ensure you can scale up quickly if it’s a hit. Having a clear lifecycle plan for each product will guide how you ramp inventory up or down and prevent obsolete stock from clogging your warehouse.

- Strategic Warehousing and Distribution: If you serve different regions or have multiple warehouses, distribute your finished goods inventory strategically. Place products closer to the demand centers to reduce shipping time and cost – for example, maintain stock at regional distribution centers if you have customers nationwide or globally. This way you don’t need a giant central stockpile; you can have smaller buffers in multiple locations, which collectively cover demand more efficiently. Modern analytics can even suggest optimal inventory allocation per location (some advanced systems use algorithms to propose how much stock to keep in each warehouse to meet service levels with minimal total inventory). By optimizing where your inventory lives, you may reduce total inventory needed while still improving delivery performance. Just keep in mind, distributing inventory means you need good visibility of stock across locations (to avoid one warehouse going empty while another is overstocked).

Implementing these finished goods practices will help you meet customer needs without waste. Customers get their orders fulfilled on time, while your company avoids money sitting in unsold products. It’s a win-win that requires diligence in planning and ongoing adjustments as conditions change.

With best practices covered for raw materials, WIP, and finished goods, you might wonder how to keep track of all these moving parts efficiently. This is where technology can play a powerful role. In the next section, we’ll discuss how using modern inventory management tools – particularly a visual solution like CyberStockroom – can tie everything together and make balancing inventory far easier and more transparent.

Enhancing Inventory Balance with CyberStockroom’s Visual Inventory Mapping

Balancing raw material, WIP, and finished goods inventory requires not only good strategies but also real-time awareness of what’s happening across your operations. This is where technology becomes a game-changer. One innovative tool that can help manufacturers gain this much-needed visibility and control is CyberStockroom, a visual inventory mapping software. Let’s explore how CyberStockroom’s features can support the best practices we’ve discussed and make inventory management more intuitive:

Visual Inventory Map for End-to-End Visibility

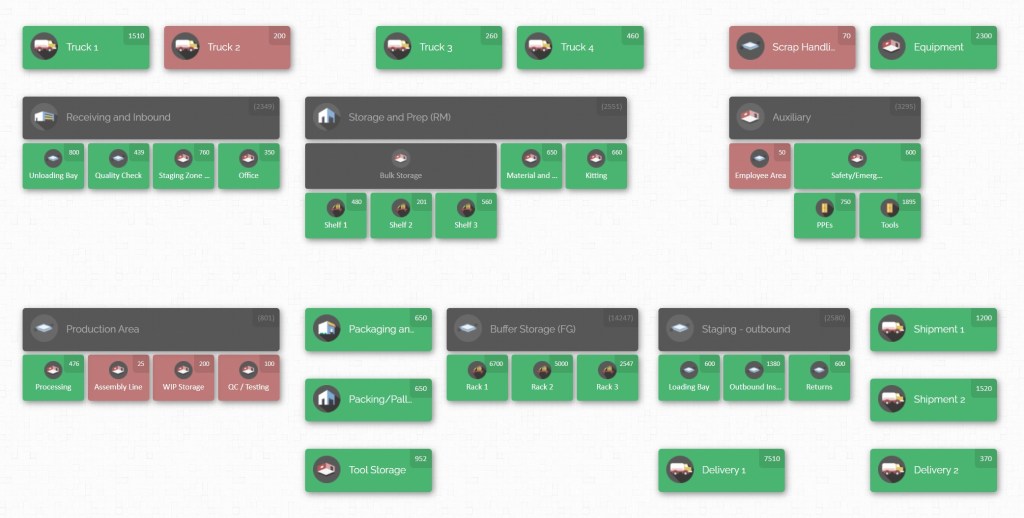

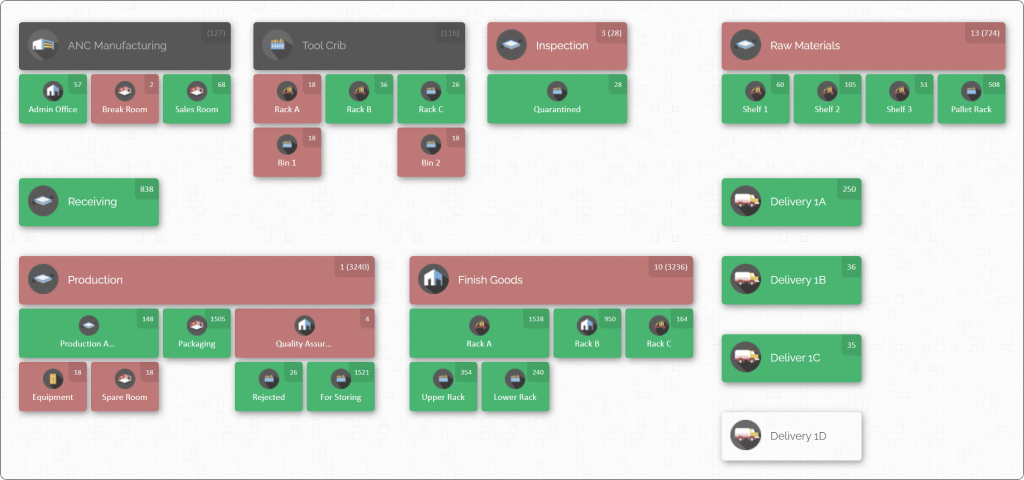

At the heart of CyberStockroom is a dynamic Inventory Map – a visual dashboard of your entire inventory across all locations and stages. Imagine opening a single map and seeing your raw materials stock in the warehouse, the WIP on various workstations in your factory, and the finished goods in storage or en route to customers. CyberStockroom allows you to create a virtual layout of your business – from warehouses to production floors to distribution centers. Each location (even a specific room, machine, or bin) can be represented on the map. This means you can literally see where everything is in real time.

For a manufacturing team, this level of visibility is incredibly valuable. If raw material inventory in the receiving area is running low, you’ll spot it on the map (often before it becomes a crisis). If WIP is building up at a particular work center, the map can show a larger-than-normal quantity stuck there, alerting you to check on a potential bottleneck. And for finished goods, you might have multiple storage points – the map shows your total stock and its distribution at a glance, so you know if one warehouse is overstocked or another is running light.

Real-Time Updates and Tracking

CyberStockroom’s system updates inventory information in real time as transactions occur. Through its interface, users can check items in and out of locations, or drag-and-drop inventory from one location to another on the map to record a movement. For example, when raw materials are issued from the warehouse to the production floor, a quick update in the system will move those items from the “Raw Material Storage” location to “WIP – Assembly Line 1” on the map. This serves two purposes: it keeps stock counts accurate and it mirrors the actual flow on a visual interface. Anyone with access (with proper permissions) can instantly know “Material A has been delivered to the floor, now 50 units are in Assembly Line 1, and the warehouse stock reduced accordingly.” Such real-time tracking means you’re always working with the latest data – crucial for making informed decisions. No more guessing or walking out to the floor to see if something has been used up; the map provides a live status.

Centralized Control Across Locations

Many manufacturing companies have inventory spread across multiple locations – be it separate warehouse buildings, different production sites, or even consignment stock at client locations. CyberStockroom’s map can incorporate multiple sites into one coherent view. Each site can be broken down into sub-locations on the map. This is immensely helpful for balancing inventory globally. Let’s say you have two factories and a main warehouse – if Factory A is low on a particular component but Factory B has surplus, you’ll spot it easily and can arrange a transfer. The software even allows you to log and track such inventory transfers between locations with a simple drag-and-drop action. This unification of data ensures that you don’t treat each stockpile in isolation; instead, you manage your inventory as a coordinated network, optimizing the balance system-wide.

Supporting WIP Visibility and Lean Practices

Earlier we emphasized making WIP visible. CyberStockroom can be configured to represent stages of production as “locations” on the map. For instance, you could have locations labeled “Cutting Station”, “Welding Station”, “Painting Station”, etc., each under a broader category like “Factory Floor”. As items move through production, updating their location on the map will show exactly how many items are at each stage. This is essentially a live WIP board. If one stage starts accumulating a lot more items than others, the imbalance pops up on the visual.

It’s like having an automated Kanban board that everyone can see. Such transparency helps teams respond quickly – maybe redeploy labor to a busy station or expedite whatever is causing a delay. It also keeps everyone honest about WIP limits because the evidence of any overload is right there on the screen. CyberStockroom’s ability to reflect process stages can effectively complement lean manufacturing efforts by highlighting flow problems and helping enforce “pull” by clearly indicating when a stage is ready for more material or when it’s swamped.

Barcode Scanning and Accuracy

CyberStockroom supports barcoding, which means you can use barcode scanners or even mobile devices to scan items into or out of locations. On the manufacturing floor, this can streamline recording of material usage or production completion. For instance, when a worker takes raw material from storage, they can scan a barcode on the material and the storage shelf; the system will deduct that quantity and show it moving into WIP. When finished goods are completed, scanning them into the finished goods warehouse updates that inventory instantly. Barcode integration greatly reduces human error compared to manual data entry, and it speeds up the process of updating inventory records. This accuracy is vital for trust in the system – when the map shows 20 units of something, you want confidence that it matches reality. By capturing transactions through scanning, CyberStockroom ensures your digital twin of the inventory aligns with the physical world.

Accessible Anywhere, Anytime (Cloud-Based)

CyberStockroom is a cloud-based platform that brings a few advantages for inventory management. Firstly, you don’t need special on-premise servers or IT to run it; you simply log in via the internet. It also means your team can access the inventory map from any device – whether on a computer in the office, a tablet on the shop floor, or even a smartphone when off-site. This is particularly useful for managers who are traveling between facilities or for salespeople who want to check stock before promising a delivery date.

The cloud nature also facilitates collaboration: multiple users can view and update the inventory status in real time. For example, as a purchase manager receives a shipment of raw materials and logs it in, the production planner can see those materials are now available without delay. In essence, everyone works off the same live inventory information, which supports better decision-making and coordination across departments.

In summary, CyberStockroom acts as a real-time command center for inventory management. By visualizing your raw materials, WIP, and finished goods in one place, it becomes far simpler to coordinate and balance them. Issues become apparent sooner, transfers and adjustments can be made faster, and everyone from floor supervisors to executives gets a clear picture of the state of operations. It’s like turning the lights on in a warehouse – once you can see everything clearly, it’s much easier to optimize it.

For manufacturing businesses seeking to implement the best practices we’ve discussed, a tool like CyberStockroom can be a powerful ally. It reinforces discipline (through clear visibility and tracking) and brings agility (through instant updates and alerts). The result is less wasted inventory, fewer surprises, and a smoother-running operation.

Conclusion

Balancing the trio of raw material, WIP, and finished goods inventory is indeed a delicate act – but one that pays off enormously when done right. By ensuring each type of inventory is kept at optimal levels, manufacturers can prevent shortages that halt production or delay sales, while also avoiding excesses that tie up cash and space. It’s about meeting demand efficiently: having what you need, when you need it, and not too much more.

We started by understanding how each inventory category functions in the manufacturing ecosystem and why none can be neglected. Too little or too much of anything – be it steel for your machines, partially-built assemblies on the line, or products in the warehouse – can hurt your business in different ways. The key takeaway is that balance minimizes risk and cost: it shields you from disruptions while keeping your operations lean and agile.

Implementing the best practices for each area creates a strong foundation. With well-forecasted raw materials, your lines stay fed without overspending on stock. With controlled WIP and smooth production flow, you shorten lead times and increase output without chaos. With smart finished goods management, you keep customers happy and free your working capital to invest in growth rather than storing unsold goods. These practices, from forecasting and supplier management to WIP limits and demand-driven production, form a toolkit that every manufacturing operation can tailor to its needs.

Importantly, the journey to perfect inventory balance is ongoing. Markets change, product mixes shift, and unforeseen events happen. That’s why continuous monitoring and adjustment are critical – and this is where leveraging modern tools is so beneficial. A solution like CyberStockroom brings all the moving parts onto one canvas, making it much easier to spot when something is off-balance and react promptly. The ability to visually track inventory through every step of the process and across all locations is a game-changer for efficiency and responsiveness. It empowers teams to collaborate and make informed decisions, backed by real-time data.

As you move forward, consider conducting an audit of your current inventory levels and workflows. Where are the pain points? Do you frequently expedite materials or end up scrapping old stock? Those are clues to where imbalance exists. Start applying some of the best practices in those areas – perhaps negotiate a better lead time with a supplier, or implement a daily WIP board meeting on the shop floor. Small changes can yield significant improvements.

Also, evaluate if your current systems provide enough visibility. If you find yourself juggling spreadsheets or lacking confidence in your inventory figures, it might be time to explore tools that can give you a clearer, more immediate picture – whether that’s an upgrade of your ERP’s inventory module or adopting an intuitive mapping software like CyberStockroom to complement your processes.

In conclusion, achieving the right “raw – WIP – finished” inventory balance is a cornerstone of operational excellence in manufacturing. It’s not always easy, but with the combination of proven practices, a culture of continuous improvement, and the aid of modern inventory management technology, it is absolutely attainable. The rewards come in the form of smoother production schedules, lower costs, faster order fulfillment, and a stronger bottom line. In manufacturing, success often boils down to delivering the right product at the right time – and that starts with having the right inventory in the right place. With the insights and tools shared in this guide, you’ll be well on your way to mastering that balance and taking your operations to the next level. Happy manufacturing!

Leave a comment