Imagine a factory where parts and materials arrive exactly as they’re needed, and finished products flow out the door without ever piling up on a shelf. This scenario is the classic vision of lean manufacturing: eliminating waste, reducing costs, and keeping operations ultra-efficient and agile. Inventory is one of the biggest wastes that lean methods target – every extra widget sitting in storage ties up capital and risks becoming obsolete. The goal is to have exactly what you need, exactly when you need it – no more, no less.

For many operations managers and plant supervisors, achieving this perfect balance is the ultimate prize. Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory management, famously pioneered by Toyota as part of the Toyota Production System, embodies this lean ideal. Under a JIT approach, materials and components arrive “just in time” for production, and products are made just in time to meet demand. When executed well, JIT can virtually eliminate the need for large warehouses of raw materials or finished goods. The benefits are substantial: lower storage costs, less money tied up in idle stock, and a faster response to customer orders. Problems in the process become immediately visible because there’s no buffer of excess inventory to hide bottlenecks or errors. In a perfect world of stable demand and smooth supply, JIT enables a company to operate with minimal fat – a truly lean inventory.

However, as many manufacturers learned in recent years, just-in-time can quickly turn into “just-too-late.” Lean purists might dream of zero inventory, but real-world disruptions have shown that running with no safety net can be risky. Global supply chain upheavals – from pandemic-related shutdowns to semiconductor shortages and port delays – taught hard lessons. If a critical supplier fails to deliver on schedule, or if demand spikes unexpectedly, a pure JIT system may grind to a halt because there are no extra parts on hand. For example, during the 2020–2021 supply crises, countless production lines stalled simply because a tiny $1 component was missing to complete $10,000 machines. As one industry expert quipped, when a $50,000 car can’t be shipped because a 50-cent chip is unavailable, it’s a sign that an ultra-lean strategy has been stretched too far. The takeaway is clear: the lean ideal of zero inventory must be balanced with practical risk management. In an unpredictable environment, flexibility and resilience become just as important as efficiency.

Just-in-Time (JIT) Inventory Management: The Lean Ideal and Its Challenges

JIT is the cornerstone of lean inventory management. Under a just-in-time system, you aim to receive materials and produce goods only as they are needed, exactly when they are needed. Instead of stockpiling weeks or months of supply “just in case,” there is a continuous flow through the operation. Parts arrive at the factory shortly before they’re used in production, and finished products are shipped out immediately after they’re completed. The result, when everything works smoothly, is minimal idle inventory at any given time.

Benefits of JIT: The advantages of JIT implementation are well documented. Companies see drastically reduced inventory carrying costs – freeing up cash that would otherwise sit in warehouses. Space requirements shrink, since you’re not storing mountains of materials or products. Waste from obsolescence or spoilage drops because items aren’t sitting around waiting to be used. Moreover, workflow tends to improve: with smaller batches and low inventory, any problem in the process (late supplier, quality issue, machine downtime) is felt immediately, prompting quick fixes. JIT often goes hand-in-hand with better quality control too, because production is so tightly synchronized that defects can’t be buffered out with stock – they must be addressed at the source. Overall, JIT can make operations incredibly efficient and responsive to actual customer demand, avoiding overproduction and excess stock.

What it takes to succeed with JIT: Achieving JIT requires careful coordination and a supportive ecosystem. Here are a few key practices and conditions needed to make JIT work effectively:

- Strong supplier partnerships: Your suppliers must be reliable and in tune with your schedule. This often means sharing production plans and forecasts with them, and possibly integrating systems so they can see your real-time needs. In a JIT setup, suppliers might deliver smaller shipments daily or multiple times a week instead of one big monthly delivery. This level of coordination builds trust and ensures materials show up exactly when needed. Close communication (and sometimes having suppliers maintain a vendor-managed inventory for you) is crucial to avoid any lapse.

- Kanban and pull signals: Many JIT systems use Kanban – a visual signaling method to trigger replenishment. For example, a Kanban card or an electronic signal might be attached to a bin of parts; when the bin runs low or empty, it automatically cues an order for more. This creates a pull system, where each process steps “pulls” what it needs from the previous step only when needed, rather than pushing materials downstream based on a forecast. Kanban ensures that inventory is replenished only at the right time in the right amount, aligning with lean principles.

- Flexible production and quick changeovers: JIT goes hand-in-hand with the ability to adapt production quickly. If you produce in very large batches or have long changeover times between products, JIT is hard to achieve because you’re tempted to build up stock. Techniques like SMED (Single-Minute Exchange of Dies) – which aim to reduce equipment setup times to minutes – are used to enable quick changeovers. The more agile your production lines (able to switch models or products rapidly), the easier it is to produce just what’s needed and nothing extra. In short, manufacturing processes need to be agile to support JIT.

- Quality at the source: With minimal inventory buffers, there is little room for quality errors. If a supplier delivers a batch of parts and a significant portion are defective, a JIT operation can come to a standstill because it doesn’t have extra stock to fall back on. Thus, ensuring high quality and “zero defects” is a key part of JIT. This might involve working closely with suppliers on quality assurance, performing quick incoming inspections, and empowering workers to stop the production line if they detect a defect (a principle known as Jidoka in the Toyota Production System). The goal is to fix problems at the source so that the whole just-in-time pipeline isn’t disrupted by a quality issue.

- Employee training and culture: JIT often requires a shift in mindset for the whole team. Everyone – from the purchasing department to line workers – needs to understand that there is no safety stock to cover up mistakes or delays. If something is running low or a problem arises, immediate action is needed. Employees on the shop floor, for instance, should be encouraged to signal any supply shortage or process delay right away (many lean factories use andon lights or alarms for this purpose). Building a culture of responsiveness and continuous improvement (kaizen) helps maintain the smooth operation of JIT. People need to feel responsible for flagging issues and solving them quickly, rather than working around them.

JIT’s Achilles’ heel – dependency on perfection: When JIT is firing on all cylinders in a stable environment, it’s fantastic. But the approach is highly sensitive to disturbances. The biggest challenge with just-in-time is that it leaves you no buffer if something goes wrong. Any hiccup can cascade into a full-blown interruption because, by design, there isn’t excess inventory to absorb the shock. A classic example often cited is a 1997 fire at Aisin, a Toyota brake parts supplier: the fire halted production at Aisin and within hours Toyota had to stop several assembly lines, because under JIT they only had a few hours’ worth of those brake valves on hand. More recently, we saw similar scenarios during global crises – factories around the world had to slow down or stop production not due to lack of demand, but because their next shipment of a critical component was stuck somewhere in a bottleneck and they had zero stock on-site. In essence, JIT works best in a stable, predictable environment with dependable suppliers and logistics. When conditions become volatile, a pure JIT system can fail to deliver.

This is where the need for flexibility in lean inventory arises. Lean manufacturing isn’t about being reckless or naive to risks; it’s about eliminating waste intelligently. The goal of “no inventory” has to be tempered by the reality that some inventory might be necessary as insurance. In practice, most companies find they must blend JIT with some strategic safety measures to keep their operations resilient.

Beyond JIT: Why Lean Manufacturing Needs Flexibility

Real-world manufacturing is full of uncertainties – machine breakdowns, supplier issues, shipping delays, sudden demand changes, natural disasters, you name it. After the supply chain shocks of the past few years, manufacturers have widely acknowledged that an ultra-lean, just-in-time-only approach can leave them dangerously exposed. As a result, many organizations are evolving their strategy to go beyond JIT, seeking a balance between efficiency and resilience.

Rather than swinging to the opposite extreme of holding mountains of inventory “just in case,” forward-thinking operations managers are adopting a hybrid approach. The idea is to remain as lean as possible day-to-day, but build in flexibility to handle surprises. In practical terms, this often means keeping a modest safety stock for certain high-risk items, diversifying suppliers, and leveraging technology for better visibility and responsiveness. In fact, industry surveys have found that a majority of manufacturing firms have adjusted away from pure JIT in recent times, incorporating more safety stock or backup sourcing for critical materials. The concept of “just-in-case” inventory – once considered almost heretical to lean purists – is making a comeback in a smart, targeted way.

Importantly, adding flexibility doesn’t mean abandoning lean principles altogether. It’s about strategically protecting the operation without flooding it with excess. Think of it like a Formula 1 race car: extremely lean and fast, but still equipped with a seatbelt and airbags for safety. You want to eliminate waste and run fast, but not at the cost of crashing your production line when something unexpected happens. The key is to identify where a little extra inventory or capacity is truly warranted and where it’s not.

For example, consider a factory that uses hundreds of common screws, nuts, and basic raw materials. These are generic items available from many suppliers on short notice. Running JIT for such items is usually low-risk – you don’t need to stockpile them because if you run low, you can typically reorder quickly or find an alternate source. Now compare that to a specialized electronic component or a custom-molded part that only a single supplier makes, with a lead time of several months. If that part is absolutely critical to your product, a pure JIT approach would be very risky. A flexible lean strategy might dictate that you keep, say, an extra month’s supply of that unique component on hand as a buffer, even while you keep everything else super lean. Similarly, some companies have started setting up dual sourcing for crucial parts – if Supplier A encounters a problem, Supplier B can step in. This way, you’re not entirely reliant on one supply line for a key item.

So how can you build this kind of flexibility into a lean inventory system without sliding back into the bad old habits of overstocking everything? Below are some tactics to achieve resilience without bloating your inventory:

Maintain safety stock for critical items: Identify which parts or materials would literally shut down production if you ran out of them. For these truly critical items, calculate a reasonable safety stock level to hold as a buffer. This might be based on factors like how variable their demand is and how long it takes to replenish. The idea is to provide a cushion for uncertainty – a little “just-in-case” inventory – focused only on the parts that really need it. For non-critical, easily obtained items, you can stick with pure JIT and have minimal or zero safety stock.

Prioritize based on risk and impact: Not all inventory is equally important. Perform a risk assessment of your supply chain and inventory. Which components have the longest lead times or most unreliable supply? Which materials have no readily available substitutes if a supplier fails? Which items are expensive if you stock out (either in lost sales or in costly expedited shipping to recover)? These are your high-risk or high-impact items that deserve special attention (perhaps extra stock or contingency plans). On the other hand, items that are cheap, readily available, or have many supplier options can be managed with tighter inventory and less contingency since the risk of a prolonged outage is low.

Strengthen supplier relationships and agreements: Work closely with your suppliers to inject flexibility into the system. You might negotiate vendor-managed inventory arrangements or emergency stock agreements where your supplier holds a small reserve for you at their site. Or arrange contracts that allow for expedited shipments or priority treatment if you suddenly need more of something. In some cases, suppliers can be geographically closer or have distribution centers near your facilities to shorten lead times. A strong partnership can also mean they give you early warnings of any issues on their end, so you’re not caught off guard. Essentially, treat key suppliers as an extension of your operation – collaboration and transparency can greatly reduce risk on both sides.

Invest in visibility and responsiveness: One of the biggest allies of a flexible lean approach is real-time visibility into your inventory and supply chain. If you can see problems brewing (like a shipment delay or a usage rate far above forecast) before you actually run out of stock, you can take action in time – such as reallocating inventory, calling that safety stock into use, or finding an alternate supplier. Modern inventory management systems and supply chain tracking tools are invaluable here. The ability to dynamically view inventory levels across your operation and across the supply chain in real time transforms how you manage lean inventory. As we’ll discuss later, having a clear, up-to-the-minute picture via technology (for example, an interactive inventory map) means you can run with lower stock levels confidently because you’re equipped to respond immediately when something changes.

In short, building flexibility into lean manufacturing inventory is about balancing efficiency with preparedness. Lean doesn’t mean being blind to risk; it means being smart about where you keep the “fat.” A small strategic buffer in the right place can save you from a massive disruption, all while keeping the rest of your operation extremely trim. Many manufacturers now talk about agility, resilience, or even “antifragility” in the same breath as lean. The goal is a system that can roll with the punches – you still aim to minimize waste and excess, but you’re also ready to adapt when reality doesn’t match the plan.

Demand Forecasting: Planning Ahead to Stay Lean

If just-in-time is the tactical execution of “only what’s needed, when it’s needed,” then demand forecasting is the strategic brain behind it. In a lean inventory environment, accurate forecasting is absolutely critical. The better you can predict what customers will order (and when), the more confidently you can cut down inventory without risking stockouts. Forecasts drive decisions on how much raw material to buy, how to schedule production, and how much (if any) finished goods to keep on hand. When you have a solid handle on future demand, you don’t need to hoard inventory “just in case” – you can rely on your data to tell you what to have ready.

On the other hand, poor forecasting can sabotage a lean effort. Overestimate demand and you’ll produce or purchase too much, leaving excess inventory sitting (waste!). Underestimate demand and you’ll run short, causing backorders or emergency scrambling for parts (risking production downtime and unhappy customers). Neither scenario is good – the lean ideal is to meet actual demand precisely with minimal surplus. Thus, investing time and resources into improving forecast accuracy is a cornerstone of building a flexible yet lean inventory system.

How can manufacturing operations improve their forecasting? Even if you don’t have a dedicated data science team, there are practical steps you can take to sharpen your predictions:

- Analyze historical data for patterns: Start with your past sales and usage data. Look for trends and seasonality. Do certain products have predictable spikes during specific months or seasons? Are there growth or decline trends over the years? Even simple methods like moving averages or basic statistical models can provide a baseline forecast by extrapolating from history. For example, if you know that every November demand doubles (perhaps due to holiday build-up or annual client cycles), your forecast should reflect that seasonal pattern so you aren’t caught short or long. Historical data is the foundation – it won’t predict the future perfectly, but it sets an informed starting point.

- Collaborate with sales, marketing, and customers: Quantitative data alone might not tell the whole story. The people on the front lines of sales or account management often have insights into upcoming demand that isn’t obvious in the past numbers. Maybe the sales team knows a big client is planning a promotion next quarter that will spike their orders, or marketing is launching a new product version that could change the mix of what’s selling. Likewise, if you have key B2B customers, they might be willing to share their projections or pipeline info with you (this is sometimes formalized in collaborative forecasting or vendor-managed inventory arrangements). By incorporating these insights, you can adjust your statistical forecast to account for known future events. Communication across departments – connecting the dots between sales forecasts and production planning – is essential in avoiding surprises.

- Use modern forecasting tools and techniques: Depending on the size of your operation, you might consider software solutions that specialize in demand planning. Many ERP and dedicated Supply Chain software systems offer forecasting modules that can automatically crunch large amounts of data and apply algorithms to detect patterns. Some advanced systems incorporate machine learning or AI, which can factor in external data (like economic indicators, market trends, even web search trends or social media sentiment for your product) to refine forecasts. While not every company needs to deploy AI, even smaller manufacturers can benefit from tools that at least automate forecast calculations and allow “what-if” scenario planning. The key is to move beyond gut feel and spreadsheets alone – although a good old spreadsheet with the right formulas is far better than nothing if used diligently. The point is to choose tools proportional to your needs that will make forecasting easier, more data-driven, and more repeatable.

- Continuously update and refine forecasts: Forecasting is not a “set it and forget it” task. One of the best practices is to implement a rolling forecast or regular forecast review process. This means you continuously update your projections as new information comes in. For instance, you might update forecasts monthly (or even weekly) based on the latest actual sales data and any new intel from the market. Track your forecast error – measure how far off you were for the last period – and investigate why. If you consistently overshoot for certain products, perhaps your model needs adjusting or there’s an unaccounted factor. If you consistently undershoot, you might need to be more conservative or add a safety margin for those items. By keeping a feedback loop (Actual vs Forecast), you learn and improve over time. The goal is to get forecasts as close to reality as possible, so you can trim inventory levels with confidence. And when unexpected events occur (which they will), you adjust the forecast promptly rather than sticking to a plan that is no longer valid.

Better forecasting directly supports a leaner inventory because it reduces uncertainty. The more you can trust your prediction of next week’s or next month’s needs, the less “extra” stuff you feel compelled to keep around. That said, forecasting will never be 100% perfect – which is why we complement it with techniques like safety stock, discussed next. But as a rule of thumb: the more accurate and agile your forecasts, the less you have to rely on large inventories as a crutch. Good forecasting is a proactive way to stay lean and meet customer demand reliably.

Safety Stock: Your Lean Buffer Against Surprises

No matter how excellent your forecasts are, the real world will always throw curveballs. There will always be some level of unpredictability in demand and supply. That’s where safety stock comes in. Safety stock is a small reserve of inventory kept on hand to protect against the unknown – the “insurance policy” for your inventory system. In the context of lean manufacturing, we want to keep this safety buffer as low as possible, but not so low that a minor hiccup causes a stockout.

The art of using safety stock is to be strategic and calculated. It’s not an arbitrary extra pile of goods – it should be determined based on data and acceptable risk levels. The basic idea is to cushion against variations. For example, if your supplier’s typical lead time is 10 days but sometimes it’s 15, you might hold a few days’ worth of safety stock to cover those occasional delays. Or if your demand for a part fluctuates, you keep a small buffer so that if demand this week is, say, 20% higher than forecast, you can still fulfill orders.

Determining the optimal safety stock level usually involves looking at two main factors: demand variability and supply variability. In more mathematical terms, companies often calculate safety stock using formulas that include the standard deviation of demand (during the lead time) and a desired service level (a target probability of not running out). Without diving too deep into formulas, the principle is that higher uncertainty (either in how much customers order or in how reliably suppliers deliver) generally requires a higher safety stock to achieve a given service level (say you want 99% certainty of not stocking out). Conversely, if your demand is very steady and your suppliers are rock-solid reliable, you can get away with very low safety buffers.

From a practical standpoint, here are a few guidelines on using safety stock in a lean, flexible inventory system:

- Target safety stock where it matters: Tie this back to the earlier idea of critical versus non-critical items. You don’t need safety stock for every single SKU. Focus on the ones that are critical to keep running or to keep customers happy. It might be finished products that customers expect within 24 hours, or key components with long replacement times. By limiting safety stock to these areas, you minimize the cost of holding extra inventory while still protecting the business.

- Don’t overdo it: It’s easy to let safety stock become a crutch that erodes lean gains. The goal is not to revert to holding a huge “just-in-case” inventory for everything. Use just enough safety stock to achieve the reliability you need. If you find that you’re holding large amounts of safety stock across the board, that’s a red flag – it might indicate deeper issues (like very poor forecasting or unreliable suppliers) that should be addressed directly. In a lean context, you should continually question and fine-tune safety stock levels. Ask: “Can we reduce this without increasing risk too much? What would it take to safely lower our safety stock – better forecasts, a secondary supplier, shorter lead time?” Ideally, safety stock is your last resort after doing everything else to make the system predictable.

- Link safety stock to service level targets: Decide on clear service level goals for different products or parts. For instance, you might decide that for your highest-priority items (maybe your top-selling product or a part that would stop your entire line if unavailable), you want a 99% service level (only 1% chance of a stockout in a period). For less critical items, maybe 95% is acceptable. These targets can guide how much safety buffer you keep. High service level requires more buffer. This approach aligns your inventory decision with business priorities and customer expectations – you’re consciously deciding where you absolutely cannot afford a stockout versus where a slight delay or shortage is tolerable.

- Recalculate and adjust periodically: The right amount of safety stock isn’t static. It should be recalculated whenever your circumstances change. If your supplier improves their delivery time consistency, you might safely reduce safety stock. If a product’s demand variability increases (maybe it’s becoming more popular but also more erratic in order pattern), you might need to increase safety stock for it. Use data from your operations: measure things like forecast error and supplier lead time variance regularly. These metrics feed into how you set safety levels. By updating these parameters, you keep safety stocks optimized – not too high, not too low – as conditions evolve.

Remember, safety stock is a buffer for uncertainty, not an excuse for sloppy planning. In a flexible lean inventory strategy, safety stock plays a vital role, but it’s carefully controlled. It provides breathing room so that a surprise doesn’t immediately translate into a crisis. By using safety stock wisely, you can handle the inevitable surprises that forecasting and planning can’t avert, without giving up the efficiency benefits of lean inventory. It’s a delicate balance – too little safety stock and you’re constantly firefighting, too much and you’re bloated – but with continuous monitoring, you can strike the right equilibrium.

Inventory Segmentation and Prioritization (ABC Analysis)

A one-size-fits-all approach rarely works for inventory management. In a manufacturing operation, you might have hundreds or thousands of different parts and products, each with different importance, cost, and usage patterns. To build flexibility into a lean inventory system, it’s important to segment your inventory and tailor your management strategy to each segment. This concept is often captured by ABC analysis or the 80/20 rule: focus the most attention on the vital few items (A’s) that have the greatest impact, and apply simpler controls to the trivial many (C’s).

Here’s how inventory segmentation typically breaks down:

- “A” items – high value or critical impact: These are the items that significantly affect your business. They could be expensive raw materials, parts with long lead times, or products that contribute a large portion of revenue. In a lean context, you still want to minimize stock of A items (especially if they are costly), but you also can’t afford to run out of them. So A items get top priority in management. You might review their status daily, forecast them with extra care, and maintain tighter safety stocks or reorder points for them. For example, a specialized motor that costs a lot and without which your product cannot be finished would be an “A” item – you’d monitor its inventory like a hawk and possibly keep a spare or two despite lean pressures, because a stockout is unacceptable.

- “B” items – moderate value/usage: B items are important but not as critical as A’s. They still warrant attention, maybe on a weekly rather than daily basis. You’ll manage them with normal lean practices and perhaps moderate safety stocks if needed. The idea is to ensure B items are under control but without the intensive oversight that A items get. Many mid-level components or subassemblies fall in this category – you care about them, but a shortfall wouldn’t shut the entire operation down (and their cost is moderate).

- “C” items – low value or low impact: These are the tail-end of your inventory: often low-cost, plentiful items or things you use very infrequently. For C items, the management approach can be much more relaxed. It might even be more cost-effective to order them in bulk occasionally and have a bit extra lying around, because the carrying cost is negligible and the risk of stockout isn’t a big deal. In lean terms, you don’t want to waste too much effort or administrative cost managing penny items with the same rigor as an A item. For instance, basic office supplies or cheap fasteners might be C items – you can reorder them in large packs occasionally and not worry about a super-precise JIT delivery for them. Simpler controls (like a periodic review or a two-bin system where you reorder when one bin is empty) might suffice.

By classifying inventory this way, you apply your time and resources where they matter most. A items get frequent cycle counts, close monitoring, collaboration with suppliers, etc., to ensure availability. C items might get checked far less frequently – you’ll tolerate a bit more inventory sitting in C items because it’s not worth the effort to trim them to the bone. This prioritization is a form of flexibility: it acknowledges that not all “waste” is equal. Carrying an extra week of stock for a 5-cent screw (C item) is not the same as carrying an extra week of stock for a $5,000 component (A item). Lean thinking encourages eliminating waste, but also recognizes you have to pick your battles and focus on what moves the needle.

In addition to ABC based on value usage, you can segment by other factors like criticality (e.g., anything that would stop production is “critical” regardless of cost), or by demand patterns (stable vs erratic demand items), etc. The main point is to differentiate your strategy. This way, you introduce flexibility by being able to relax lean rules slightly for some items while enforcing them strictly for others. For example, it may be perfectly fine and lean-consistent to keep a larger buffer of a rarely-used spare part (because if it’s needed it’s urgent, and the cost of holding one is low), whereas you keep no buffer at all for a common component you can get next-day easily.

Segmentation also leads to actions like SKU rationalization – examining whether you have inventory items that are slow-moving or unnecessary. Perhaps you have multiple versions of essentially the same part because different engineers ordered slightly different ones; rationalizing could mean standardizing to one part to reduce inventory complexity. Or if a product is a slow seller, maybe you shift it to a make-to-order model instead of stocking it. All of these decisions help streamline the inventory and reduce waste, while ensuring effort is spent where it counts. By pruning and organizing your inventory intelligently, you create a more flexible system that’s not bogged down by managing every SKU equally. You focus on the vital parts of the inventory that truly need attention.

In summary, inventory segmentation is a powerful technique in lean inventory management. It helps maintain flexibility by aligning effort and resources with business impact. You remain lean by not overstocking or over-managing trivial items, and you remain safe by giving critical items the buffers and oversight they require. The outcome is a more optimized inventory that supports lean goals without courting disaster on the important things.

Leveraging Technology for Lean Inventory Flexibility: CyberStockroom’s Approach

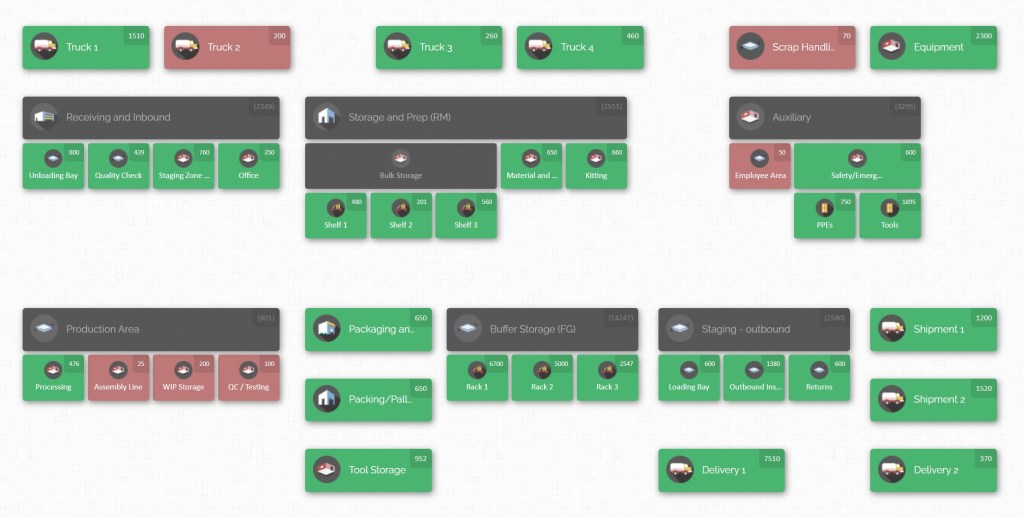

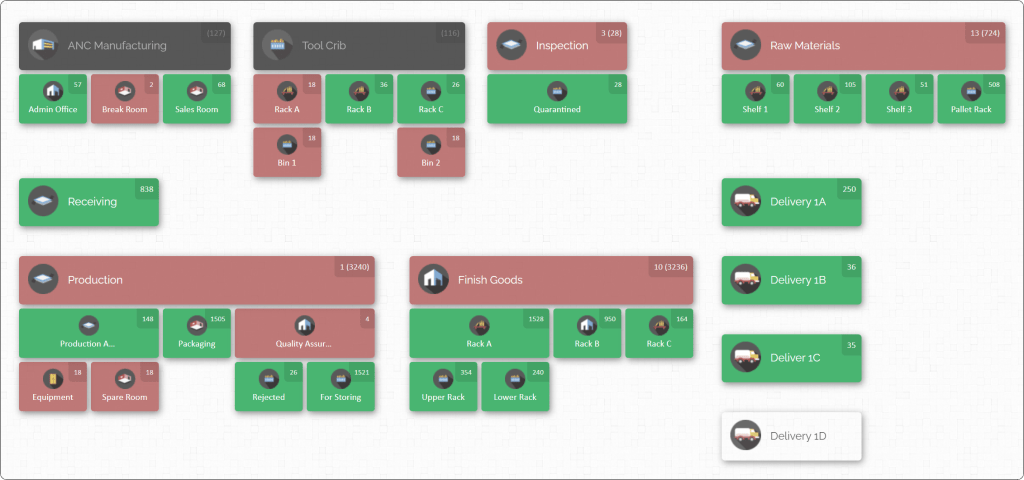

Executing all these strategies – JIT, safety stocks, segmentation, etc. – relies on having accurate information and the ability to respond quickly. This is where modern inventory management tools become essential. One such tool is CyberStockroom, a cloud-based inventory management platform that uses a unique map-based interface to give you real-time visibility of your inventory across locations. Let’s discuss how leveraging a tool like CyberStockroom can help build flexibility into a lean manufacturing inventory system:

Real-time, end-to-end visibility

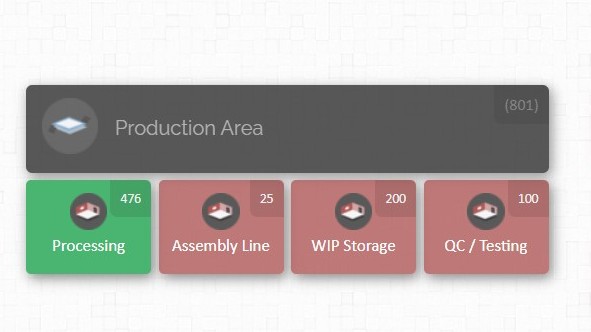

In a lean environment, knowing exactly what you have and where it is at any moment is crucial. CyberStockroom’s visual Inventory Map provides a bird’s-eye view of your entire operation’s inventory. You can see all your warehouses, production areas, storage rooms, and even vehicles or staging areas represented on a map, with counters showing current stock levels. This kind of visibility means no more guesswork or hunting through spreadsheets – if a part is running low in one location, you’ll spot it immediately on the map.

Having this transparency helps prevent surprises. For instance, if a machine operator flags that they’re almost out of a component, a manager can glance at the inventory map and see if there are more of that component elsewhere in the facility (or at another site) that can be reallocated, or if an urgent order needs to be placed. Essentially, CyberStockroom acts as a central dashboard for inventory, which is incredibly valuable for lean operations that can’t afford to lose time due to unknown stock positions.

Location-based tracking and control

CyberStockroom doesn’t just list what inventory you have; it ties each item to a specific location on the map. This is great for manufacturing because it mirrors your physical workflow. You can map out your factory floor – for example, raw materials in Warehouse A, Work-in-Progress (WIP) at Station B, finished goods in Dock C – and then manage inventory by location. This is very much in line with lean principles of visual management. Anyone can look at the map and understand the state of inventory in each area.

Say there’s supposed to be a buffer of 50 units in a certain assembly area – if the map shows only 5 units there (maybe with a red alert indicator), it’s a clear signal to refill that area. CyberStockroom allows setting thresholds and alerts, so if a location’s stock falls below a set level, that location can be highlighted. This is akin to a digital andon signal for inventory: it immediately draws attention to a potential problem so you can act on it. By managing inventory in a location-specific way, you maintain the smooth flow that lean manufacturing demands. Materials get to where they need to be, when they need to be there, and the software helps coordinate that.

Drag-and-drop simplicity and quick updates

One of the challenges in staying lean is keeping inventory data accurate as things move rapidly. CyberStockroom’s map interface allows users to drag and drop inventory icons from one location to another to record transfers. For example, if you move 100 units of a component from the warehouse to the assembly line area, you can simply drag that item on the map to the new location, and the system will decrement the source and increment the destination – updating stock levels in real time. This intuitive approach means your inventory records stay perfectly in sync with physical reality with minimal effort. It also encourages teams to actually make the updates (since it’s easy and even visually satisfying) rather than postponing data entry. The result is an up-to-the-minute accurate inventory picture, which is something you absolutely need to successfully implement JIT and flexible responses. There’s also a check-in/check-out feature, which can be useful if, say, tools or equipment are moving around or if you temporarily assign materials to a project and then return unused parts back to stock. Keeping these movements transparent and easy to log helps prevent the “missing inventory” syndrome that can plague operations.

Barcode scanning integration

While CyberStockroom is map-centric, it also supports traditional inventory management capabilities like barcode scanning. In a lean operation, speed and accuracy of transactions (receiving, issuing, picking) are important to avoid delays and errors. With barcode integration, workers can scan items into or out of locations, and the inventory map will update accordingly. This reduces manual errors and makes things like cycle counts or audits much faster.

For instance, you could walk around with a barcode scanner or a mobile device and scan everything in a particular zone; CyberStockroom will reconcile the counts and highlight if something’s amiss. Regular cycle counting is a lean best practice (to catch discrepancies early), and this system makes that process more efficient, meaning you can do it more often without heavy effort. The outcome is confidence in your data – you trust that the quantity showing on the screen is what’s actually on the shelf. That trust enables you to keep lower inventory levels because you’re not keeping “just-in-case extra” to compensate for unknown shrinkage or record errors.

Multi-location and multi-warehouse coordination

Many manufacturers operate across multiple sites or at least multiple storage areas (production floor, main stockroom, off-site warehouse, etc.). CyberStockroom’s map can include multiple facilities or sub-locations within facilities, all in one view. This is extremely useful for flexibility. If one plant faces a shortage, you can quickly check inventory at a sister plant or warehouse. Perhaps you can redistribute stock between locations to avoid an emergency purchase. Or if demand shifts regionally, you see where inventory is sitting and can plan to re-route it. Without a tool like this, companies often end up with silos – each site ordering extra “just in case” because they lack visibility into the company’s overall stock. CyberStockroom breaks down those silos by giving a holistic picture. This allows a leaner overall inventory because you can pool buffers or at least be aware of where your slack is.

Enhanced decision-making through data

Over time, CyberStockroom collects a lot of useful data – movements of inventory, dwell times at each location, usage rates, etc. The system offers reporting and analytics that can help identify trends or inefficiencies. For example, you might discover through data that a certain part is always languishing in a subassembly area for weeks – indicating overproduction or a bottleneck downstream. Or you might notice you’re frequently transferring a particular item from location A to B to cover shortages, suggesting maybe location B’s reorder point should be higher or supply flow should be adjusted. This insight supports continuous improvement (kaizen).

The map itself is a living visualization that can reveal patterns – maybe Work-in-Process is accumulating in one corner of the map, hinting at an imbalance in production. By having your inventory and workflow visualized, discussing improvements becomes easier; teams can literally point to the map in meetings and collaborate on optimizing the flow.

Accountability and traceability

In industries where traceability is important (e.g., aerospace, medical, food manufacturing), CyberStockroom can track lot numbers or serial numbers and their location. If there’s a quality issue or recall, you can quickly see all affected materials on the map and pull them from use. Also, because every transaction in the system can be tied to a user and timestamp, there is accountability. You know who moved what, when, and where. This tends to encourage more responsible handling of inventory (no one wants to be the person who didn’t log that they took the last box of parts). In a lean system, problems are ideally exposed and addressed, not hidden – this kind of transparency software enforces aligns with that philosophy.

In summary, CyberStockroom enables the kind of agility and control that a flexible lean inventory system demands. It gives you the real-time eyes on your stock (so you can run leaner without fear), the ability to quickly update and adjust (so your data stays accurate through fast changes), and the analytical support to keep improving. It’s not that technology replaces good lean practices – rather, it bolsters them. CyberStockroom acts as a digital backbone for your inventory, supporting JIT by providing confidence in tight inventories, and supporting resilience by alerting you to issues and letting you respond swiftly. By leveraging such a tool, operations managers can have the best of both worlds: the efficiency of lean inventory and the flexibility to handle the unexpected.

Putting It All Together: Steps to Build a Flexible Lean Inventory System

We’ve covered a lot of concepts and tactics – now let’s consolidate them into a step-by-step strategy. Whether you’re revamping an existing system or building a new one, here’s a roadmap for implementing a lean yet flexible inventory management approach in a manufacturing operation:

- Assess Current Inventory and Identify Waste: Start with a clear-eyed evaluation of your current inventory management. Where do you see excess stock piling up? Which items seem to always linger unused, and which ones cause emergencies when they run out? Map out these pain points and quantify the waste (e.g., how much capital is tied in slow-moving stock, how often have stockouts halted production). Set clear lean goals – for example, “reduce total inventory value by 20% within a year while maintaining service levels” or “cut stockouts to less than 2 per quarter.” This gives you target outcomes to strive for as you implement changes.

- Strengthen Demand Forecasting: Before cutting any inventory, shore up your forecasting process. Gather historical sales/usage data, involve stakeholders (sales, marketing, planning) for qualitative insights, and implement a regular forecasting routine. You might choose a forecasting tool or just improve your spreadsheet models, but make sure there’s discipline in how forecasts are made and updated. A solid forecast is the foundation for all lean inventory decisions – it informs what “should” happen so you can plan inventory accordingly. Put in place a monthly (or weekly) review of forecasts vs actuals to keep improving accuracy. Essentially, get as good a crystal ball as you can, because running lean without knowing what’s coming is a recipe for disaster.

- Implement Lean, Pull-Based Replenishment (JIT where feasible): Gradually shift your inventory replenishment to a pull system. This might involve introducing Kanban cards or signals on the production floor, reducing order batch sizes, and working with suppliers on more frequent deliveries. It can be wise to pilot these changes on a small scale first – for instance, pick one production line or product family to transition to JIT ordering and see how it goes. During this phase, maintain open communication with your suppliers and your team, since their cooperation and buy-in are crucial. The goal here is to start trimming the fat: reduce those big stockpiles of parts by replacing them with a steady trickle that aligns with actual consumption. Monitor the results (inventory levels, lead times, any stockouts) and refine the process before rolling out more broadly.

- Establish Safety Stocks and Contingency Plans: As you remove the bulk of inventory through JIT, identify which areas need a safety net. Calculate initial safety stock levels for critical items using your data (forecast errors, lead time variability, desired service level). Set up reorder points that incorporate these safety stocks so that you’ll replenish in time before hitting zero. At the same time, think about contingency: do you have backup suppliers for key materials? Have you discussed emergency options with current suppliers? Put those plans in place now. This step is about making sure that as you lean down, you aren’t leaving the operation exposed. Document the rationale for each safety stock so it’s clear why it’s there (for example, “Item X: keep 200 units safety stock due to 8-week lead time and volatile demand”). This documentation will help later when you revisit and adjust these buffers.

- Classify Your Inventory (ABC or Similar): Segment your inventory into categories (A, B, C) or whatever scheme makes sense (like critical, important, low priority). Use criteria like annual usage value, criticality to production, or replacement lead time. Then apply differentiated policies: For A items, maybe you review their status daily, set high service level targets, and keep tighter safety stock. For B, weekly checks and moderate targets. For C, perhaps a bi-monthly review and minimal safety stock or none at all. Also, identify if any SKUs can be trimmed from your catalog or combined. If you find you have five variants of essentially the same item, consider rationalizing to one to simplify inventory. The outcome of this classification step should be a clear focus – you and your team know which items to really watch like a hawk and which items can be managed with a lighter touch.

- Leverage Inventory Management Tools for Visibility and Control: Invest in a system to help manage all this complexity. This could be an inventory module in your existing ERP, or a specialized solution like CyberStockroom that provides a visual map and real-time tracking. The tool should support what you’re doing: alert you when something’s low, allow easy updates when stock moves, and give a consolidated view of inventory across your operation. By adopting technology, you enforce the lean processes – for example, automatic low-stock notifications ensure you don’t miss a replenishment, and centralized data prevents different departments from hoarding “just in case” stock unbeknownst to others. When evaluating tools, look for features like multi-warehouse support (if you have several locations), barcode scanning (to speed up data capture), and user-friendliness (so that team members actually use it consistently). The right system acts like a nervous system for your lean inventory: sensing issues, transmitting information, and even taking routine corrective actions (like generating a reorder).

- Train the Team and Build a Lean Culture: Even the best processes and tools will fail if people aren’t on board. Take time to train all relevant staff on the new approach to inventory. Explain why the company is doing this – for example, how lower inventory frees up cash, or how lean practices reduce waste and firefighting, ultimately making everyone’s job easier and the company more competitive. Specifically train them on any new processes (like how to use Kanban cards or the new inventory software). Emphasize the importance of timely updates – e.g., “If you take parts out of stock, it’s critical you log it immediately so our system stays accurate.” Encourage a culture where employees feel responsible for flagging issues (if a part is always almost stockout, speak up; if a process feels cumbersome, suggest a change). Recognize and reward behavior that supports lean principles, like an operator who comes up with a clever way to reduce changeover time or a storekeeper who consistently keeps the inventory records spot-on. Building a culture of continuous improvement and vigilance means the lean inventory system won’t erode over time – instead, it will get stronger.

- Monitor Performance and Continuously Improve: Once your flexible lean inventory system is in motion, use metrics to track its health. Key metrics might include inventory turnover (how many times you cycle through inventory in a year – higher is generally better for lean operations), service level or fill rate (what % of orders are fulfilled without stockout), frequency of stockouts or production stoppages due to part shortages, and inventory carrying cost (how much money is tied up in stock and associated holding costs). Also monitor things like supplier lead time reliability and forecast accuracy, since these directly affect your performance. Set up regular reviews – maybe a monthly operations meeting where you review these KPIs and any incidents (like “we had a stockout of part Y last month, why did that happen?”). Use these reviews to identify areas for adjustment: perhaps you discover forecast error for a new product is high – you might increase safety stock on it until forecasts improve. Or you notice an item consistently has excess – you could try reducing its reorder quantity. Lean is an ongoing journey, not a one-time project. By continuously tweaking your forecasts, inventory parameters, and processes based on real data and feedback, you will inch closer to the optimal balance. Over time, what’s “optimal” may also change as your business or environment changes, so this step never really ends – continuous improvement is part of the DNA of lean thinking.

Following these steps creates a loop of planning, execution, and feedback. You plan (forecast demand, set policies), execute (order and produce in a lean way), then get feedback (measure results, spot issues) and feed that back into planning by adjusting parameters or strategies. Starting small – for example, implementing these changes for one product line or area – can build confidence and demonstrate results, which you can then scale to the broader operation. As you progress, you’ll likely find that lean inventory management becomes second nature, and the benefits (both in cost savings and in operational agility) will motivate the team to continue refining the system.

Conclusion

In today’s competitive and fast-changing manufacturing landscape, inventory optimization is a balancing act – the art of doing more with less without tipping over. Lean manufacturing taught us how to trim the fat: eliminating excess inventory, reducing waste, and focusing on efficiency. But recent years have also reinforced the importance of resilience and agility. The sweet spot for modern operations lies in blending the efficiency of lean with the robustness of a safety net. It’s about being efficient and being prepared.

By implementing a flexible lean inventory strategy, you stand to reap significant rewards. You’ll likely see lower carrying costs and more cash freed up, since you’re not tying money in mountains of stock. You’ll reduce waste – less expired, obsolete, or overproduced inventory taking up space. At the same time, you’ll experience fewer emergencies like line shutdowns or panicked expediting, because you’ve built safeguards (like targeted safety stocks and alternate plans) against those scenarios. The operation becomes more agile – when customer demand changes or a supply issue pops up, you can respond swiftly rather than being stuck with your hands tied.

For operations managers, plant supervisors, and supply chain professionals, turning inventory management into a competitive advantage is a game-changer. Instead of inventory being a constant headache (“Why do we have so much of X sitting her e?” “How did we run out of Y again?!”), it becomes a well-tuned part of your machine. Delivering the right product in the right quantity at the right time – consistently – earns trust from your customers and eliminates a lot of internal firefighting. Yes, achieving this balance requires effort: it means rethinking processes, investing in the right tools, and continually educating your team. But the payoff is a smoother running operation and more peace of mind.

The journey to lean and flexible inventory is ongoing. Conditions will keep changing – new market demands, new disruptions, new technologies – and the companies that thrive will be those that continuously refine their approach. By staying data-driven in your decisions, maintaining visibility across your supply chain (with help from tools like CyberStockroom’s inventory map), balancing efficiency with smart buffers, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement, you can edge closer to the ideal of “just-in-time” performance without being caught off guard by the unexpected. In other words, you’ll achieve the efficiency lean manufacturing strives for, while still being ready with a backup plan when reality throws a curveball.

Inventory management isn’t just an operational task – done right, it’s a strategic advantage. With the strategies outlined in this article, you can move beyond the old JIT paradigm and build a resilient, flexible lean inventory system that keeps your production running like clockwork and your customers happy, no matter what challenges arise. Embrace the journey of ongoing improvement, and you’ll find your operations becoming not only leaner and more cost-effective, but also more responsive and robust in the face of whatever comes next.

Leave a comment